I arrived with my family. I handed the usher our tickets.

We entered the auditorium. The stage was lit. We were directed to our seats.

We were there to watch an OPAS Junior production—a performing arts play for families and children.

The performance would soon be what we paid for, an enjoyable Sunday afternoon event with my wife and boys.

The actors and actresses did their job. They appealed to us, the audience. They danced, sung songs, provided humor, and so forth. They were there for us that day. And, we were there for them.

We paid for their performance. And, they gave us one.

* * *

A compelling strategy has consumed American healthcare. It’s known as pay-for-performance. It’s trying to replace our unknown fee-for-service model, because it seems more logical.

We’ve been told incentives that favor hip replacement surgeries for joint pain over weight-loss encouragement are the problem with healthcare. So, the solution, is to get away from paying for each intervention done.

Instead, pay for the health benefit, provided to the population, as measured by whatever.

Reimburse when the joint pain for a large group of people is improved. Don’t fund surgery after surgery. Less is more a lot of the time, people will say.

Of course, where one finds Logic, one frequently will encounter Illogic, too.

For example, in almost everything we do, we accept paying per hour worked, per lawn mowed, per haircut given, per item purchased, and so forth.

Pay-for-performance in healthcare disregards much of that. Yet, many support the scheme.

Those that do are often connected in some way to the bureaus actually judging the performance. In fact, groups linked to these groups have been proliferating for some time.

For pay-for-performance to even have a scheme, data must be collected and compiled like never before. So, data groups emerge. More computers are needed, so information technicians abound. A myriad of quality organizations pop up. Lots of things to further crowd the crowd—many duplicating and overlapping with government dollars what others were legislated to do.

Take, for example, medical licensing. It’s a simple concept familiar to most of us. Admittedly, few understand the degree to which government-issued medical licenses have increased medical costs, but that’s not my point today. When asked, most of us think medical licensure by the government is a needed and successful process. Oddly enough, the government’s own actions on this matter appear to disagree.

Think about it. The intended purpose for involving government with medical licensure was to ensure the quality of medical care provided. If government oversight on this matter had really worked, we would have no need for 962 more pages explaining new legislation outlining complex doctor grading schemes set to start-up next year. In fact, if a government program wasn’t the closest thing to eternal life on this earth, state medical licensing could have been expunged with an addendum on page 963 altogether.

The point I’m making here is that lots of dollars have been invested in this pay-for-perforance strategy. You might be shocked to know that physician practices in the United States now spend $15.4 billion annually just reporting so-called quality measures! Who knows how much other entities are spending for the same purpose.

So, who is paying for all of this?

You and I.

Yet, most of us still remain dangerously oblivious to this obvious fact.

So, what benefits are we receiving?

Well, that’s the bombshell.

A recent study analyzing the success of pay-for-performance at U.S. hospitals says that it has failed. It doesn’t work. These facilities aren’t providing any more “quality” by using mandated pay-for-performance models. None at all.

The results aren’t even surprising.

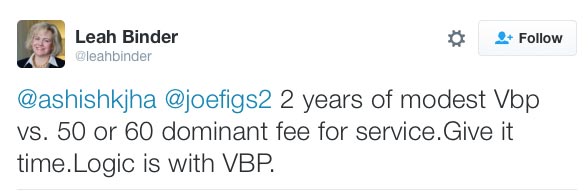

The findings merely echo other studies that have said the same thing here and elsewhere. Pay-for-performance, or value-based purchasing (VBP), just isn’t working. But, trust me, those inexplicably tied to this investment have no intention of letting it die:

It’s actually three years, Ms. Binder. We’ve been doing it for three years. England has been doing it for eight. But, I get your bias. It’s opposite from mine.

“We just need to do MORE of it for MORE time,” you say. And, I’ve got no doubt you’ll be on this train—whether it’s logical or illogical—until the bitter end.

As for the rest of us, we are going to consider the following.

The government’s pay-for-performance plan is essentially a budget neutral proposition. Here’s how it works. Withhold payments to hospitals and doctors. In effect, issue penalties to all participants upfront. Then, redistribute the retained funds to the “highest performers,” based upon some unproven, and often rather schizoid, metrics.

This is the plan. The one you will be hearing more about.

It’s the very same concept that (regardless of intention) has historically failed to improve quality: it’s known as redistribution of wealth. It’s not pay-for-performance at all. It’s socialized medicine.

Acutal pay-for-performance would require the person experiencing the performance to be the one directly paying for it. We call that a market. It’s what has driven quality and increased standard of living from our default impoverished beginnings more than anything else.

It’s why, of Americans still designated as “poor” today, Mitt Ridley notes “99% have electricity, running water, flush toilets, and a refrigerator; 95% have a television, 88% a telephone; 71% a car and 70% air conditioning.” The wealthiest in the world just over a century and a half ago had none of these.

Patients paying doctors is actually the one pay-for-performance scheme that is working. The trend is taking hold. Many are creating and finding their own prosperity in market-driven healthcare, and those who do, shouldn’t be mandated to participate in another failed government project.

You can think what you want, but anything outside of patients paying physicians is really just a scam insulated by numerous bureaucratic and heavily politicized obstacles. And, when you remove them, you will find—quite ironically—that pay-for-performance oddly resembles fee-for-service.

* * *

I imagine with trepidation an alternative reality.

It takes place in the near future when I attend with my family another OPAS Junior production.

Yet, this time, we have no tickets.

It’s free.

Or so it seems.

It’s really just free because we’ve already had the money taken from us long ago. So much money taken, in fact, that we can no longer afford to arrive in the vehicle we previously purchased.

Instead, we arrive, like all the families, having been picked up by a school bus.

We enter the auditorium and find our seats. The actors and actresses begin their routine as before, but their motivation is different this time. Their focus is not on us.

They dance, but each movement is directed toward appeasing a critic far away. They sing, but their voices are more tired now. Their humor lacks its delivery.

What a performance this will be.