Visions define us.

Viewpoints alter our assessment of the facts.

Mine. Yours. All of ours.

The more we realize it, the more productive our discussions will ultimately be.

Sometimes, visions affect us so much so that we have no real interest in empirically reviewing what we already want to believe. Evaluating and re-evaluating the reality created by our beliefs intrigues us very little. We prefer to see the evidence that supports our vision. And, we ignore the rest.

A clash of visions plays out all around us—economically, politically, and socially. Here’s one example in the debate over healthcare reform policies.

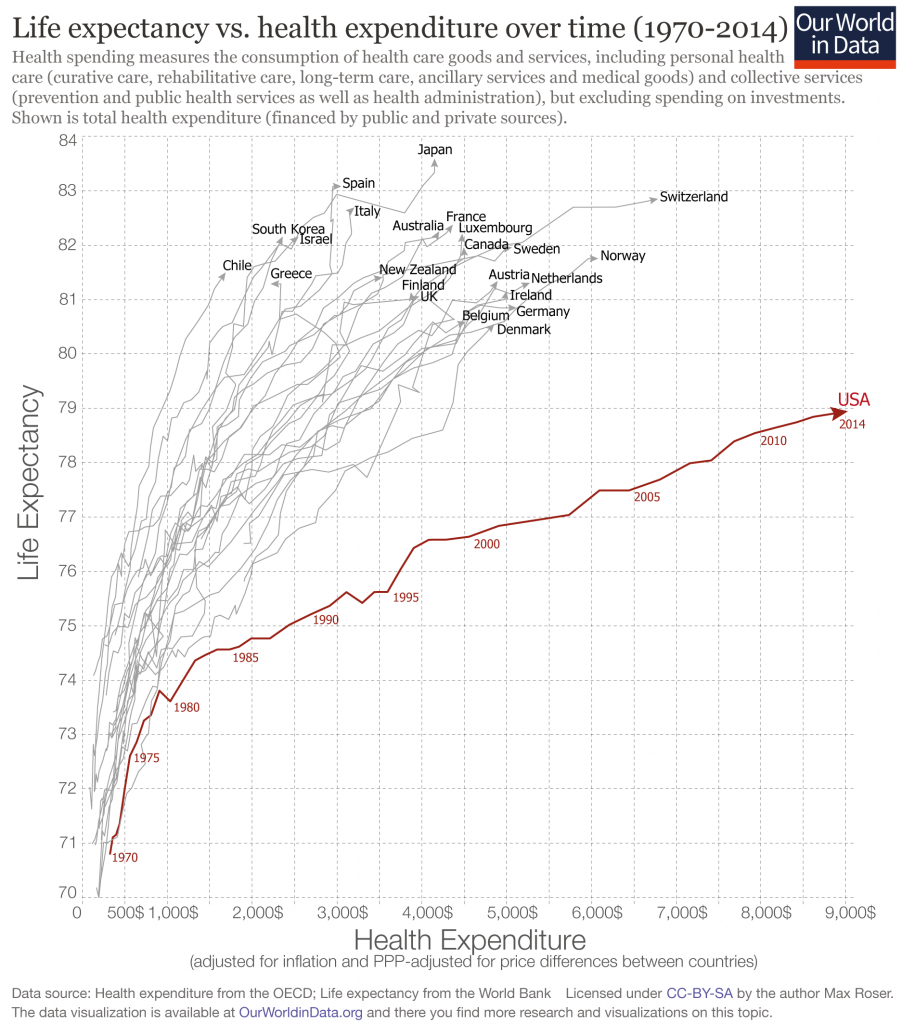

l’ll begin with this graph from Our World in Data:

The X-axis is health expenditure. The Y-axis is life expectancy. The United States appears by itself at the bottom-right of it. And, here we go…

One, who happens to have One’s vision, inevitably concludes:

1. “Americans pay too much for lousy health outcomes.”

This is a common conclusion, yet One’s vision takes it a step further.

It presumes the graph to be a reflection of medical care, a.k.a. what doctors can do for you. The assumption being that we do too much (overuse), and this makes our health quality poor.

But, do other facts speak to a different conclusion?

Outsiders behave as if we have the best medical care in the world. Affluent foreigners, who could go anywhere, visit all the time to receive it from us.

The reality is that medical care and health care—and how these two relate to life expectancy—are two entirely different things. Any attempt to presume they are interchangeable on this graph is erroneous, and conclusions gathered from doing so are much the same.

Unlike what doctors can do for you, health care, to a large degree, involves what you can do for yourself—what you decide to eat, your habits, and your lifestyle. Cultural and ethnic influences aside, any group of people (in this case, Americans) who tend to be more obese, sedentary, consume more drugs, and have more homicides, might expect to find themselves far below other groups on the Y-axis of life expectancy, irregardless of healthcare expenditures.

Although it may enhance the rhetoric of One’s vision (that we are dying from overuse) by plotting these variables alongside each other, justifying causation requires mystical assumptions akin to those explaining weather patterns by flapping butterfly wings.

Separating the U.S. from the other countries on the graph requires no added hysteria, only a single dimension.

Just the X-axis is needed.

You will find the U.S. all by its lonesome by looking at spending alone.

Americans pay too much, but ironically, we don’t spend it directly on ourselves.

We predominantly give it to third-parties—the government, insurers, and so forth. Then, we turn around and attempt to wrestle back from them the care we think we deserve.

2. “Profit-driven healthcare must go.”

One’s vision needs no understanding of economics or constrained human behaviors to exist.

For this reason, it frequently misconstrues the purpose of profits altogether.

Profits merely reflect the value added by entity A to resources X, Y, and Z, to produce a given product or service for someone to use or consume.

Profits, in effect, are what enable Walmart to deliver a handful of pencils to you for a few quarters. And, not just pencils. Refrigerators, televisions, and numerous other highly technological things are amazingly affordable to the vast majority because of profits.

Profits drive wealth creation—historically far more beneficial for the least fortunate than wealth redistribution. The more iPhone 7s we produce, the more people can suddenly afford iPhone 6s, and so forth and so on, until iPhone 2s are basically just given away.

Profits aren’t the issue. Historically, the attempt to arbitrarily fix them, or establish central control over them, is what invites the cronyism that differing visions equally despise.

The great travesty comes not out of profits themselves, but from creating an elitist authority to police them.

Such apostles (in the name of “misused autonomy”) mistakenly try to “correct” the very system (marketplace) that is already allowing for the wills of ordinary people to prevail. What gets overlooked by One’s vision, in order to shake-another-stick at profits, is not inconsequential: reallocating the power of millions of little hands into the palms of a few, paradoxically deprives the “lesser” people the most.

3. “Take better care of the dying… When people die slowly attached to machines in the hospital or in nursing homes, everyone loses.”

Maybe. But, that frequently depends on who is keeping score.

The patient? The caregiver? The patient’s family member? Do our ethnic and cultural variances on this matter suddenly become negligible? Are we all in agreement with some universal understanding of death and dying?

“We don’t have to deny care to the elderly—just tell them the damn truth.“

One’s vision commonly assumes there’s but one way we should die. But archeological facts show us more than one civilization has developed an alternate reality about this uncertainty.

It’s just hard to even scratch the surface on this one, but I’ll try.

I’ve seen end-of-life heroic resuscitation measures be therapeutic to grieving families even when I (the caregiver) believed them to be futile. I’ve seen patients reassured by my promise to fulfill their wishes and “do everything I can” to save them. I’ve seen us (as caregivers) do too much. Almost never have I seen end-of-life care be done for financial gain alone.

I’ve been asked by patients’ families to do (in my own mind) too little. And, I’ve done what didn’t feel right at the time, only to think later that it was entirely necessary.

“Just tell them the damn truth” may be a part of One’s vision, but if the fate of our healthcare system rests upon reconciling this one, we should be more pessimistic now than ever.

4. “Slow the growth of non-caregivers.”

Amen, to that! Diverging visions agree. But One’s vision is not reconcilable with this goal.

To successfully politicize and attempt to oversee the complexities involved with centrally procuring healthcare for the masses, one must allow for the never-ending expansion of bureaucratic power.

One must bring back the idea that “some are meant to be booted and spurred in order to ridden by another.”

The very notion of central control provides the necessary rationale for bureaucratic expansion, the likes of which have already become painfully evident throughout the U.S. healthcare system.

From documentation requirements to electronic medical records, from certified pseudo-quality metrics to onerous licensing requirements, the mark of these expansions—much like those in public education—have been to reduce options and constrict freedoms of those delivering and receiving the services.

Is the vision really more important than the reality it creates?