I wrote previously about the ongoing federal approval process for a medical device known as the WATCHMAN™, now available to treat certain patients at risk of stroke.

As expected (and really just because it’s how things get done around here) the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has compiled a 32,000 word decision memo related to how it intends to pay (if at all) for patients receiving this approved device. This memo is commonly referred to as a coverage determination.

A thoughtful piece was also written recently by Dr. John Mandrola on this very topic. He and I usually share many of the same goals, although admittedly, we differ from time to time on how best to obtain them.

Regardless, Dr. Mandrola’s piece is full of clarity and is very supportive of CMS’s intent to require an evidence-based formal “decision tool” to be used by the physician and the patient prior to implanting the WATCHMAN™.

The CMS memo states:

A formal shared decision-making interaction between the patient and provider using an evidence-based decision tool… must occur prior to [device implantation], must be documented in the medical records… [and so forth, with full text found here after scrolling down one page]

Decision tools, or aids, can be very useful.

They often exist in the form of pamphlets or software, frequently accessible through the internet. You probably have used something similar if you ever sought to buy a television online. It’s the “click here to learn which TV is right for you” link.

The basic goal of a decision aid in healthcare is to make patients aware they have a choice, explain the “evidence” surrounding each choice, and better examine how each choice relates to their own desired values.

I routinely implement many forms of decision aids when I discuss treatment strategies with my patients. I draw pictures. I reference charts. I occasionally show videos. I often engage patients with number-needed-to-treat scenarios (e.g. “if one-hundred people somewhat similar to you were in the room with us today, five may experience XYZ over the next year if left untreated… ninety-five, of course, won’t…”).

To me, making decisions like this with my patients is what I’m supposed to be doing as their doctor. It’s just me doing my job.

And, I’m more convinced than ever now, that creating another formal CMS requirement about doing my job doesn’t add anything but more paperwork to the process.

Support for decision aids is obviously another one of these admirable concepts. Who can argue with that?

But, I’ll tell you that quantifying which decision aids are best because of whatever “evidence,” and then mandating their use before a decision can be made, is a much mirkier chore… and one that CMS should stray far from.

Many patients don’t know this, so I’ll tell you.

Whenever I evaluate you in my office for anything–your particular symptom, your disease, your need for a medicine, or to discuss a procedure with you–CMS already has created a 48 page paper telling me what I must document about the visit. They explain what I should examine and what I must put into my note. And, it’s just ridiculous (not to mention exceedingly inefficient) having to do it their way most of the time. I can only imagine how many more pages CMS will add in order to describe what decision aid is worthy of use.

Last week, I witnessed a social media discussion about whether or not a patient’s gait (i.e. how someone walks) should be added as a “fifth” vital sign. Proponents of this clerical addition said there was “evidence” for it–that gait was critical to patient outcomes of all types, especially for those patients undergoing procedures. Therefore, it should be a vital sign.

You probably know that assessing gait is already part of the comprehensive physical exam now. So, why not move it to the top, next to blood pressure, start double-documenting it there, and make it another quality metric?

Friends, we need another CMS metric like we need a hole in our head.

We need good practicing doctors. Not institutes of retired doctors thinking up more pillars of care. Besides, 32,000 words from CMS and another mandated metric about decision aids won’t make this madness any clearer. It will just further propagate our race to expand an already bloated documentation world, and give even more fodder to those already hijacking evidence-based medicine.

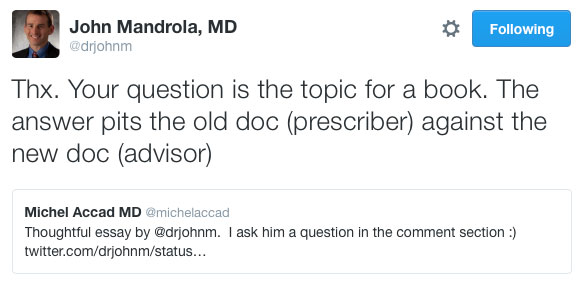

Dr. Mandrola astutely writes that the best medical decisions may not be what the guidelines say, and he is spot on. But, he also comments that “patients are experts in what is best for them,” prompting Dr. Michel Accad to ask him an interesting question:

If patients are experts in what is best for them, what do they need doctors for?

Dr. Mandrola’s response below is fantastic, noting the answer lies within a book pitting the “old doctor” against a “newer” one.

Perhaps, that’s true. But, maybe there will always be a need for both the prescriber and the advisor. And, to the dismay of more CMS mandates seeking to standardize practice patterns, it seems the best answer will always need judgment. I just think it’s time to quit supporting whatever takes that away. Even if that something is so-called evidence.

* * *

Earlier today, I was finishing up my visit with Mr. G.

I was in the midst of doing what I always do. I was drawing some pictures, making some gestures with my hands, and recreating an understanding of the heart’s anatomy by pointing to different parts of the wall.

Noticing that Mr. G was losing interest in my production, I paused.

“What are your thoughts, Mr. G?” I asked.

“What the hell are you asking me for, Doc?” Mr. G responded with his characteristic grin. “You know what’s best. Let’s do that.”

And so, with one fell swoop, I became the prescriber.

With it, came more pressure on me to choose wisely than ever before.

But, that’s okay. It’s my job.