Often, things aren’t what they seem.

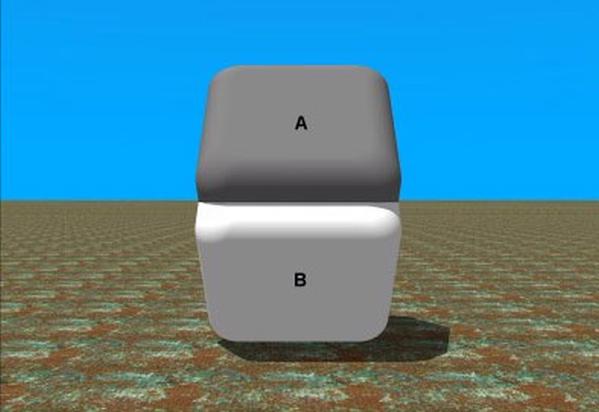

Take the image above, for example. Which shade of gray is darker? A or B? Look closely. I wouldn’t want you to miss this one.

Now, place your finger horizontally between A and B. Cover up the transition zone between the letters. Block the area with all the shadows. Look again.

Very interesting, right? The two colors are the same. Remember, things aren’t always what they appear to be. In fact, when you find yourself on the side of the majority, you should think even harder.

We already discussed causation and correlation, but it’s time to go deeper than that. Stuff just happens all the time for reasons that we seem to miss. We assume the problem is one thing. At least, it appears to be acting that way on our stage. But, if only we could see deeper. Far below the surface. Would we see things the same way?

I read a Harvard Magazine article last week. It said that doctors’ beliefs in unsupported medical therapies are costing our healthcare system hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

“Cowboy doctors are a problem,” it claimed.

The article got my attention. I couldn’t immediately recall any “cowboy doctor” curriculum taught at my medical school, but I kept reading. America’s vitamin and supplement industry is a mere $37 billion one, so I was curious how much “wastefulness” the authors were going to attribute to patients’ own beliefs in less-proven modalities. But, the article mentioned none of that. It remained laser focused on the Wild West.

The article commented that most “cowboy doctors” weren’t being cowboys for extra income or financial reward. They were being cowboys because they couldn’t accept a dying patient, and they just had to do something.

The doctor just felt the need to do something.

Now, before you decide that you might actually prefer cowboys doing something for you in a time of need, know that one author’s solution was to financially penalize them. Basically, “tax” doctors who behave like cowboys for overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Why? Because, on the surface, this always sounds like a great idea.

The obvious problem becomes how best to judge overtreatment. Who determines a case of overdiagnosis? Me? You? Population health epidemiologists? People who blend the dots that comprise all of us but care for none of us? Maybe.

But, what if I told you that the real problem isn’t what you think it is at all. What if I told you that the waste in our current system, cowboys included, stems from an obsession we’ve been fostering in medicine for some time.

THE PROBLEM WITH OVERDIAGNOSIS

You are a middle-aged, sedentary, man interested in beginning an exercise program. You have risk factors for heart disease and come to visit me in my office to ask if it’s safe to start exercising vigorously.

After much discussion, you and I make the decision to first monitor you while walking briskly on the treadmill in my office. If you are going to have any problems with your heart, maybe it’s better that it happens then, while under close observation.

During this treadmill evaluation, I notice some concerning changes on your heart rhythm tracing. You become very short-of-breath, but think that you can keep walking further. I decide to stop your test early. It’s significantly abnormal.

We visit in detail about these findings and make the decision to perform a couple more tests on your heart. Ultimately, I end up diagnosing you with heart disease. I counsel you further and make the decision to start you on three new medications. One is available over the counter. The other two both cost about the same each month as a caffe latte from Starbucks.

You begin taking the pills. I repeat your treadmill test in my office. I see improvement, and I now recommend a fitness program for you to begin doing at home. You take my recommendations, and onward we go in life. Together.

But, here’s the rub. We know you have heart disease, but did I overdiagnose it? You weren’t having any symptoms just sitting on your couch. Am I being a cowboy? Did I overtreat you with my procedures and my medicines?

Maybe. Maybe not.

But, how do we really know? The truth is that we won’t know for a long time.

“I will challenge you to show me one case of overdiagnosis,” says Dr. Michel Accad. And, he’s right. Overdiagnosis is a hypothetical construct. We can only assume it has taken place after the fact, usually years down the way. And, you really need to get this point in order to understand mine.

People having no symptoms on the couch may walk on a treadmill and get diagnosed with heart disease. Then, in about forty years, we might be able to assume that they were overdiagnosed. But, that will only happen when, or if, the expected benefit of this group fails to materialize against some other group that might be comparable.

Think about it.

Why do we know that the probability of getting heads on a fair coin toss is fifty-percent? Because you can toss that same coin 1,000 times and prove it to be true. The very same coin. Over and over again. We can verify it.

Medicine is different. The individual patient can never undergo repeated flips of a coin. Each patient is unique. You can’t flip a willful being 1,000 times to verify a universe of possibilities. Life is not a Choose Your Own Adventure book. And, for this reason, when it comes to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of an individual patient, it’s anyone’s guess.

LOOKING FOR A BALANCE

Johnnie came to visit me today. Her blood pressure was 149/84 mmHg. It’s her second reading in my office at this level in recent weeks. One major medical society that publishes blood pressure recommendations says I should treat this patient with medication. Another says I shouldn’t. Even another says that it depends.

The truth is that Johnnie lost her spouse a couple of months ago. Other things are going on that deserve more attention. But, that is almost blasphemy in the eyes of government-mandated healthcare quality metrics. Penalize those physicians who don’t think Johnnie’s blood pressure is important. Shame on the doctors for ignoring it. This has become our current system.

“If doctors restrict themselves to performing what is evidence-based,” said one of the non-physician authors of the Harvard Magazine article above, “we can save hundreds of billions of dollars a year.”

In Johnnie’s case, there’s no consensus what even is “evidence-based.” What I do know is that doctors around the country are racing around every day treating asymptomatic blood pressures, just like Johnnie’s, in the name of public health. And, for what absolute benefit? For what absolute cost?

Clearly, the pharmaceutical industry appreciates our obsession with this type of public health. We frequently treat hundreds of people like Johnnie on the off-chance that we could help even one. In fact, here’s some real evidence for you. Each day, I see just as many patients in my clinic who are having side effects from blood pressure medications than I see who really need them.

Any chance this could be part of the problem?

I don’t want you to get confused with my message. I’m not telling you blood pressure management is unimportant. I’m a cardiovascular specialist. In fact, I’m the one you see when someone else has difficulty controlling your blood pressure. I’m well-trained on how to manage it.

But, what if I told you that we have gotten our principles all mixed up.

What if this misstep is costing us dearly?

What if value-based medical decisions were never intended to be directly made from the comfort of remote academic or governmental towers? What if this is the real problem we are failing to see?

Instead, what if medical decisions were allowed to take place as they were intended, between individual patients and individual healers. What if together in the office and at the bedside, by utilizing the greatest knowledge of time and place, these two parties were better able to balance medicine’s needed connection between the arts and the sciences?

Would this balance more easily achieve the dual goal of cutting costs and improving quality?

On this point, I am not certain.

But, here’s where my clarity returns. Ultimately, you can please only one master. As a physician, we are now being asked to pick. Whom shall it be? The insurance company? The government authority? The hypothetical group? Or the patient?

Not choosing the patient just may be empowering the deadliest cowboy of all.