Cancer screening has NEVER been shown to save lives.

That’s the eye-catching title of a recent article emanating from Academic medicine.

I liked it.

I’ve known for some time that we bother too many patients with absolutely no symptoms of disease under the guise of Evidence Based Medicine (EBM). So, of course, I started reading it.

The lead author has been involved with other discombobulating publications of statistical mumbo-jumbo. So, naturally, I wondered what sensible and non-sensible use of statistics I’d encounter.

It didn’t take long for me to find both.

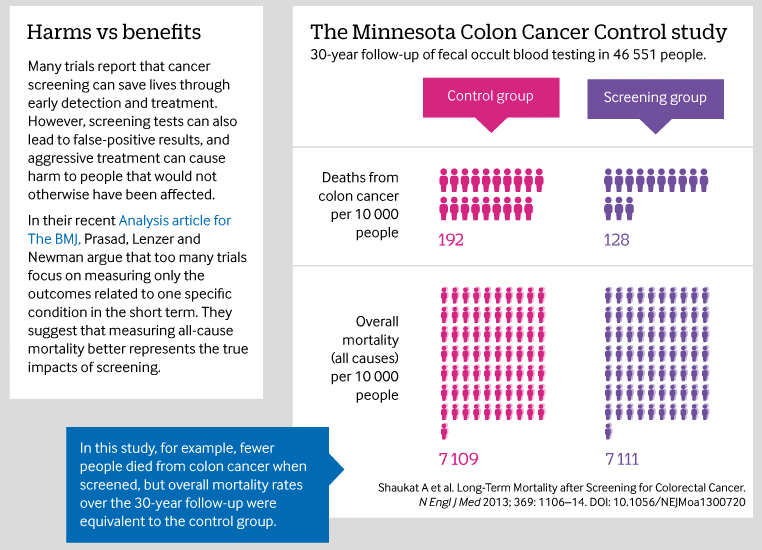

The article opens with an infographic summarizing the presumed benefits (based upon one study) of screening for colon cancer with a simple, non-invasive, test that looks for hidden blood in your stool. We call it fecal occult blood testing (FOBT).

Now, don’t get too caught up in all the text below. Just look at all the little people on the right side of the infographic:

One caption next to the little people reads “Deaths from colon cancer.” The other reads “Overall mortality,” which means any death from any cause.

And, yes, here’s what it wants you to know:

Screening for colon cancer reduces deaths from colon cancer. But, you will still die. Regardless. From one thing or another.

I’ll say it again.

Screening people (with FOBT) for colon cancer may reduce their chances of leaving life because of colon cancer. But, they will still leave life due to something, at a statistically similar rate, whether they’re screened or not.

Basically, the article’s authors want you to believe that while screening reduces some deaths, it must (in some way) cause others. But, really, the fundamental principle at work here isn’t too hard to follow. I’ll break it down for you.

In fact, here’s what was done in the original study from which the infographic was derived:

1) Take a bunch of people who are, on average, about 62 years old.

2) Screen some with a test. Don’t screen others.

3) Screen some people once a year for eleven years. Screen others twice a year for 6 years. Collectively, call them the screening group. The non-screened people will be the control group.

4) Now, let time pass.

5) Now, let even more time pass.

6) Keep track of no additional tests, screening studies, colorectal procedures, or other medical stuff that gets done to anybody after a handful of screening years are complete.

7) Then, check back in 30 years.

What will you find?

That most people are dead by then. No matter what was done. Just less people in the screening group died specifically from colon cancer.

So, case closed.

Screening NEVER has been shown to save lives.

* * *

The authors go on to mention a few other statistical compilations in their quest to prove the point already made by their infographic. And, their assumptions just may be true. But, I challenge you to read the original articles from which they make their conclusions.

For example, take the use of mammography for breast cancer screening. Eleven individual trials were mentioned in the article they referenced. All but one trial found a numerical decrease in breast cancer deaths with screening mammography. Two of the trials even showed statistically significant reductions in all-cause death.

How many of the trials showed statistically “proven” harm and increased all-cause death with screening mammography? None.

Here’s another example.

Take the use of ultrasound to screen for an aneurysm in your belly (something called an abdominal aortic aneurysm). The same article they cite analyzed the results of four clinical trials. All four showed numerically fewer deaths from aneurysm rupture in those getting an ultrasound procedure. All of them also showed numerically fewer all-cause deaths in the group getting screened.

You see why your angle matters when you report the evidence?

It always matters.

In fact, the analysis (specifically called a meta-analysis) used for this paper’s conclusion about aneurysm screening was selected because it had the longest follow up. That’s right. Kind of like the infographic above. Pick anything tracking life long enough, and things will always tend to converge toward the inevitable… death. Interestingly, despite this fact, the meta-analysis still revealed a 45% relative risk reduction in aneurysm-related death and a 2% relative risk reduction in all-cause death in those who were screened.

Again, your angle always matters.

And, trust me. There’s plenty of controversy related to screening procedures. But, don’t let anyone fool you. Most of it relates to cost effectiveness.

And, yes, since healthcare exists within an outrageous stratosphere of costs inflated by third-party payment (including our government’s), people quoting costs are rarely certain what they are even quoting.

Pricing is so far disconnected now from individual value that everything is really just like cancer screening–one discombobulated web of confusion.

You see, the authors of the infographic article go to great lengths to make it crystal clear to you that performing a chest X-ray, to screen for lung cancer, won’t save lives.

But, rather ironically, this so-called evidence-based fact of population medicine doesn’t disprove the subjective truth that ordering a chest X-ray on Bob, in my office today, is the right thing to do. It doesn’t help reconcile the fact, that this strategy–for reasons that don’t find their way into a statistical equation–provides “value” to Bob, today.

How do I know?

Because, I know Bob.

And, frankly… you don’t.

* * *

Think about it this way.

You were taking Medicine X, but it had too many side effects for you. I changed it to Medicine Y. Now, you are doing fantastic, but it’s January 1st of a new year.

Your same health insurance company has made some modifications to your prescription plan. They will no longer pay for Medicine Y.

Why?

Well, they claim the “evidence” says the side effects for Medicine X and Medicine Y are the same.

“Are they the ones taking it?” you ask. Because, you already know such evidence is nonsense. At least for you. You are the one getting the side effects.

But, the reality is that you have no say. And, ultimately, neither do I as your doctor.

You see, that’s basically the way of central authority healthcare. Whether the government runs it or not, that’s a single-payer system. And, yes, that’s nonsense.

* * *

Almost amusingly, the infographic’s angle toward cancer screening is ultimately similar to mine. I will likely choose to do less, rather than more. Most doctors do. But, whatever I decide, it will inevitably be based upon varying degrees of both sensible and non-sensible statistical understanding.

So, I’m not telling you to get a mammogram. I’m not telling you for which cancer you should be screened. Most of those things aren’t my area of expertise, anyway.

But, I’m telling you to find a good doctor. And then, support a system that allows for him or her to treat you as an individual, instead of toward the mean.

You see, we need clinical trials. We need intelligent lead authors combing through their data. But, not for the purpose of proving less is more. Not for the purpose of determining what boxes should get checked inside an electronic medical record.

We need these things, ultimately, just for Bob.

And, obviously, spending billions of government dollars to develop complicated physician payment schemes, built around ordering certain screening tests that may or may not even be helpful, is not the answer.

Having the Health Department issue actual grades to physicians based (in part) upon their participation level and performance on certain screening measures, is a philosophical error that ultimately penalizes the individual patient more than anybody.

You see, the nuances of medicine will never be mastered by regulatory onslaught.

Actually, this is what is killing us.

Not screening procedures.