HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Quality in medicine appears to have been formally first addressed around the 4th century B.C.E. in a collection of approximately 60 treatises known as the Hippocratic corpus. These writings outlined diagnostic methods of physicians but also detailed treatment failures for the benefit of all.

The corpus’s most famous surgical text, On Fractures, opens with a promise to discuss mistakes:

“I must therefore mention which of the physician’s mistakes I want to teach you not to do.”

The quest for quality throughout the corpus was distinctly a personal matter, centered on humility and the challenges of medicine:

“Life is short, the art is long, opportunity fleeting, experiment perilous, judgment difficult.”

This is one of the most famous statements of the Hippocratic corpus–its focus noticeably removed from a world-group or professional responsibility.

As we entered the Middle Ages, the relationship between medicine and church had grown to be strong. The Body and the Soul were viewed as “one.” The Body, the physical object that can be touched and measured. And, the Soul, that intellectual and willful being, less easily grasped. These two entities had become one and the same, and quality depended on being able to treat them together.

By the 16th century, however, our Western viewpoint began to shift. We transitioned from medicine being an art to more of an empirical science. “Nothing matters that cannot be measured or quantified,” became the new mojo. And, since the Soul couldn’t be grasped, it had to be separated out. Our focus shifted almost solely toward the Body as medicine became a science. The Body was really just a machine for observation and experimentation. You want to fix the patient? Fix the defect, and it will fix the machine. And, find a way to standardize the operation.

With medicine being performed more and more within institutions by the 19th Century, the new hospital work environment further molded responsibilities away from the individual, away from the Hippocratic emphasis on personal humility, and toward group responsibilities.

Professional ethics.

Medical professionalism.

Tracking this, tracking that.

And, these concepts by themselves aren’t bad things. They arose, at least in part, from our inherent quest to improve things.

In the 20th Century, medical education received what seemed to be a much needed overhaul regarding qualifications for entry. The Food and Drug Administration was established, setting standards for prescription medicines. By the 1950s, several organizations joined together including the American College of Surgeons, the American College of Physicians, the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, and the Canadian Medical Association to form the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals, now known simply as the Joint Commission, all in the name of improving quality.

Modern evidence-based medicine was born; basically the concept that statistical evidence gained from a finite few can drive standardized therapies for populations of people. By the mid-1980s Congress had created the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, that would help to create clinical practice guidelines to guide physician decision making, standardize practice, and improve health-care quality.

Population-based medicine, basically what’s “good for the group is good for the individual,” would became the cornerstone of managed care, with the overriding emphasis on cost-containment and access to massive amounts of data.

In 1996, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) would unveil an initiative to improve the nation’s healthcare quality, and at the turn of the 21st century, it would release its magnum opus, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, which summarized earlier findings regarding medical errors. This report famously alleged that as many as 98,000 American’s die every year due to medical errors in U.S. hospitals.

The 98,000 number was derived by a single report that retrospectively analyzed a sample of charts from several New York State Hospitals in 1984, 16 years before the Institute of Medicine report was published.

Regardless, the report found approximately 150 deaths that occurred due to potentially preventable causes, and extrapolated this number to the number of patients hospitalized, not in New York, but in America in 1997, and came to the 98,000 people number.

The New York Times didn’t delve into the details of any of this, but was quick to comment that medical deaths due to errors in this country are the equivalent of having “three jumbo jets filled with patients crash every two days.”

Almost overnight, patient safety organizations, both private, government-funded, and government-controlled, would spring up, attempting to put their stake in a system-based approach to once again try and satisfy our ongoing thirst for excellence.

In summary, over the last two millennia, we’ve seen quality in medicine transition from a physician’s individual focus on humility and personal virtue, to a professional society’s collective concern built upon the emphasis that medicine is an empirical science, and finally to a system-based approach with a myriad of both new and old stakeholders, with arguably the most powerful one currently being our federal government.

GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT IN HEALTHCARE

Last year, government-funded health insurance, specifically Medicare and Medicaid dollars, comprised about 39% of personal healthcare expenditures in this country. And, I get it. If you pay for something, you want to know what you are getting. One way to do this is to regulate production, or for that matter, design the product entirely yourself. Implement a takeover.

But, how good are you at doing what you have decided to take over? Are you the best at doing it?

We all want quality. And, to be honest, we’ve always strived to find better ways to deliver it.

But our history with quality in medicine over the last couple millennia has also had long periods of stagnation. And, the question that we must ask ourselves now is: “Are the current methods being used actually missing the mark?”

MEASURING QUALITY IN MEDICINE

Keep in mind, no one doubts that measuring quality in medicine is challenging. And why is it so challenging? Because, as Dr. Michel Accad eloquently explains in a number of his short essays, medicine, at its very root, is about healing. And, healing encompasses both the Body and the Soul!

You see, the aim of science is to acquire knowledge. The aim of medicine? It’s to heal. And, these two things are not one in the same.

Don’t let me confuse you. One way you can heal is to use scientific knowledge that you believe you’ve obtained by observation and experimentation. It’s one of your tools, but it’s not the only one. In fact, personal involvement through caring, may work even better sometimes. But, that’s hard to grasp. It’s hard to measure. It deals with the soul.

But, my point is not to lose you with philosophy, so I’ll be more direct. In order to truly assess quality in medicine, you have to start my making two assumptions, both of which are inherently inaccurate:

1) Values are the same for everyone.

2) Data is absolute.

I’ll say it again. Values are the same for everyone. And, data is absolute.

Let me explain.

To declare that the same therapy should be provided to all, to claim what’s good for the group is always good for the individual, you must be able to assign scores to the things that patients value. And, these scores? If our therapies are to be standardized? They must be weighted the same for everyone. We must make the assumption that quality can be defined similarly for each unique patient. And, this assumption is erroneous.

Quality for you will never be entirely the same as quality for me.

For example, you are feeling weak today. It’s because you are anemic. Your blood count is low. I’m your doctor. I know that. And, I think you need a blood transfusion. This should improve how you feel. It will provide quality to you.

But you don’t see it that way. Your ideals are different. Your perspective is unique. From your viewpoint, a blood transfusion places impure substances from outside your body into your body. Giving you this transfusion is not quality to you at all. It’s detrimental to a more important value judgement.

I had an interesting discussion with someone recently about measuring quality. We agreed that value is challenging to measure, but I was told that “mortality is not subjective.”

I answered by reminding this person that “How you live your life, is!”

And, you don’t have to just delve into religious preferences to see this fact running rampant. Values just aren’t the same for everyone, which makes it impossible to represent them entirely by a formula.

But, even if we had the same values… which is our inaccurate assumption number one… how are we going to quantify the values? By using scientific data? Sounds reasonable.

Data that is absolute? Sure.

Then, show it to me? Because, as Dr. Robert Centor reminds us, the philosophy of logic says it doesn’t exist.

If X is a direct and logical conclusion of the evidence, different panels of experts would arrive at the same guideline recommendations for the same clinical problems. But, this doesn’t happen. Different panels develop differing guidelines all the time. Many times they strongly conflict with one another.

You need this screening test. No, you don’t.

How can this be?

Because evidence is never absolute. Data must be interpreted. And, how do we interpret it? By using our own unique value-system!

One of my favorite examples of the wide discrepancies with data interpretation comes from a landmark trial in my own field of cardiology known as the COURAGE trial. The trial enrolled people with heart disease, people with a blockage in their coronary artery, and they were treated either with procedures like the placement of a stent, or with medical therapy. Stents versus medicine, if you will.

Here’s one headline that appeared in the lay press summarizing the findings of this study:

Stenting is not superior to medical therapy.

Here is another one, from a different source, about the same study using the same dataset:

Stenting is superior to medical therapy.

Which is right? Well, they both are. How is that? Well, it depends on how you value superiority.

Do you care about lives saved? Or symptoms relieved? Or quality of life surveys? Do you want the competition between the groups to end at three years or at five years? Does it only matter to you if statistically we’re 95% certain that the results didn’t occur by chance, or are you okay if just 90% certainty exists?

Does it change your perception if I tell you that 1 out of 3 patients in the medical therapy arm didn’t just get medicines as a therapy? 1 out of 3 actually underwent an interventional heart procedure during the study just like those in the stenting group did. Yet, their outcomes were counted toward those assigned to the medical therapy group, because that’s the type of statistical analysis we chose as being valuable for this study.

Does your opinion about using conclusions from this trial to establish “guidelines” for everyone in town change when I tell you that 94% of the entire population screened for this study weren’t even enrolled in the study? Only 6% of the people evaluated in the given patient population were even randomized and participated in the trial’s data collection process.

I could go on and on, trial after trial, but the conclusion is the same: there is no absolute data. There is only interpretable data.

THE GOVERNMENT TAKEOVER & HOW IT’S WORKING OUT

Values aren’t the same for everyone. Data is not absolute. Medicine is not solely an empirical science. But, for arguments sake, just assume these things are true. Derive a formula to measure them. Oh wait, that’s what we’ve been trying to do a whole lot in the last few years.

The government’s takeover of quality in medicine has established all types of formulas and quasi-quality metrics, and the government has levied all types of financial penalties on physicians if they don’t comply. Tons of resources are being devoted away from actual patient care to charting and submitting one variable after another to a central bureaucrat for analysis.

I think the best question then to really ask ourselves, is how we are doing at that? Are our incentives positioned in a way that appear to be making a difference? Or, are the current incentives actually creating more obstacles in our quest for quality.

Take, for example, your cholesterol, specifically your LDL, is 70. That’s great. Or is it? I’m not sure. How much value is that number really providing you. And, is it value for whom?

You? Or, the pharmaceutical company? Or me, the doctor, because I get credit for “healing you” when it’s at this level? Major experts can’t even agree on this one. And, it will likely change again next year.

You see, even if values are the same, data is absolute, and medicine is merely a science, you can’t evaluate quality at this time by tracking micro-managed measurements ten-parts removed from absolutely anything that matters to a patient; it’s like trying to determine how advantageous the flapping wings of one particular butterfly might be to the weather patterns half-way around the world. You should throw out metrics like this one and dozens upon dozens of others others that have no role being tied to physician payments.

I’ve been on the front lines of patient care for over a decade now. I know the quality of data that has been submitted and still is being submitted in the name of “patient safety.” In fact, I literally have quit reading retrospective studies of claims-based data that has been submitted to our government. The information by which their conclusions are based is just unintelligible garble.

Now, you can argue that we just need to keep pumping more money into this project until we can get it right. Just need more institutes of value and more missionaries for quality. I think you are wrong.

THE LAW OF BUREAUCRATIC DISPLACEMENT

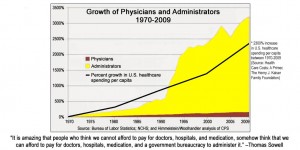

The slide on the right charts the percent growth of administrators verses physicians over the last four decades. The administrators are in yellow. The physicians? You might not be able to find them. They are the smudge of a line at the bottom.

The slide on the right charts the percent growth of administrators verses physicians over the last four decades. The administrators are in yellow. The physicians? You might not be able to find them. They are the smudge of a line at the bottom.

When did the two colors explode in divergent ways? In the early 1990s, for around that time was the passage of the Medicare Fee Schedule, with its use becoming mandatory in 1992. Payment for medical services suddenly became highly dependent on an extravagant scheme of codes, invented precisely to convey to remote government bureaucrats what is taking place in the privacy of exam rooms and hospital bedsides.

And, we can keep doing more of this. Bring in more people who can develop and decipher more codification. In fact, in recent years, about the only thing in medicine that hasn’t been moving toward a philosophy of “less” is “more,” is the bureaucratic mandates.

For example, my group private practice has already devoted thousands of dollars and vast resources to prepare for the likely implementation later this year of the most byzantine cipher system to date, ICD-10. To account for ICD-10’s existence, every patient’s note in my electronic medical record now requires, on average, an additional one to two dozen clicks on the screen. Every single one.

Yes, we can keep doing more of this. We can keep pumping more money into building more clicks, in order to measure more quality metrics, founded on erroneous principles, to yield more unintelligible facts to exploding numbers of central bureaucrats, placed in charge of determining the health of a population. But, for the value of what?

Or rather for the quality of whom? The individual? The government-funded health insurance plans? The government-lobbying big-businesses of healthcare?

Or maybe, perhaps real quality is just about creating ultimate accountability. Maybe the latter is all we are seeking. Accountability to patients that I, as their personal doctor out of humility, will do the very best that I can do every day in medicine for them.

And, you better believe there are better and less expensive ways to show accountability than what we’ve done in recent years by attempting to measure pseudo-quality metrics.

Maybe, my eleven years of medical training after college is not enough accountability for some people. I don’t know. Maybe medical board certifications matter. Maybe not. All I know is that I’ve never once had one of my patients actually ask to see any of the five board certifications that I have paid money to obtain.

I’ve never had one ask me how many of my patients have an LDL less than 70. I guess that I must achieve accountability to them by some other means, which is precisely my point.

86% of health care leaders recently surveyed said their meetings are a waste of time. I am a healthcare leader and I’ve been to those meetings and I’ll share with you why I believe they’ve become meaningless: government influenced ideas for quality. They’ve got a number of names, and nearly all have an acronym:

PQRS, MIPS, ICD10, MU, APM, and so on.

The vast majority of what we are doing in modern day healthcare meetings is self-proclaimed futility. Our focus is not on the patient directly, but instead, it’s on a bunch of acronyms.

You remember the Institute of Medicine’s report at the turn of the 21st Century that alleged 98,000 deaths per year were due to medical errors? You remember all those patient safety organizations who have been established since then, all these checklists that have been created, all these central bureaucratic employees who’ve been hired, and all these government-driven so-called quality mandates?

Well, a more recent study in 2013, using just as fuzzy math I might add as the Institute of Medicine’s report did, claimed that we are now at 440,000 deaths per year in America due to preventable medical events.

With an apparent 5-fold increase in medical errors since the advent of the patient safety and government quality takeover movement, one may wonder if the methods currently being employed are not themselves part of the problem.

In confusing the patient with the jumbo jet, as Dr. Accad says, are we needlessly distracting health care personnel from their most precious and unpredictable cargo?

Is the government’s takeover of healthcare quality actually leading us to the biggest medical error of them all?

Has our focus away from the humility of the patient-physician relationship toward more prideful and poorly measurable outcomes, caused us to lose our sight in medicine?

Have we lost our focus on the patient?